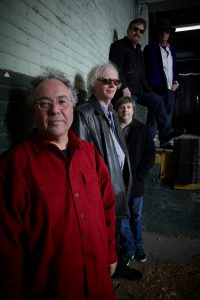

Kim Rancourt

Kim Rancourt goes walking along the beach at Coney Island most every Sunday morning. Picking through the seaweed and the broken furniture. He’s found 8,000 Barbie dolls, a motorcycle and a carpet of flowers that leaked out of a fractured container vessel. He even found Harry Connick Junior out there one morning, and when they met they talked about Kim’s career in music. Kim Rancourt sees stuff you might miss and finds value in things you don’t see.

Kim Rancourt goes walking along the beach at Coney Island most every Sunday morning. Picking through the seaweed and the broken furniture. He’s found 8,000 Barbie dolls, a motorcycle and a carpet of flowers that leaked out of a fractured container vessel. He even found Harry Connick Junior out there one morning, and when they met they talked about Kim’s career in music. Kim Rancourt sees stuff you might miss and finds value in things you don’t see.

Kim Rancourt gets paid to give tours of New York City, and that makes sense because he is a storyteller and cheerleader for the place. Well, no—there’s a lot of stuff that drives him crazy about NYC, but that’s part of his story, too. He knows the unpretty landmarks of New York City, where the noise gathers, and the backstory of Luna Park. Plus more.

Look what washed ashore today: plum plum. He’s led bands and been on a clutch of records, but plum plum is the first one to come out under the name Kim Rancourt. He wrote all the words, he and the band wrote all the music. About that band: they’re pretty good! Starting with Don Fleming, the guitarist (B.A.L.L., Gumball, Velvet Monkeys) and deal-maker who assembled this klatch. “Don knew in his head exactly what he wanted,” says Kim. “Don put the band together. Of course when he mentioned who he wanted to bring in I said, ‘uh yeah.’ He felt that we didn’t need any guest stars on the record—this band was great enough.” Uh: YEAH. Joe Bouchard, founding bassist of the Blue Oyster Cult and studio savant, may be the most valuable player. “The album was mostly made live in the studio but the genius is Joe Bouchard—he is one hell of a musician and one hell of a nice guy.”

Also in attendance is fellow Michigander Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth): “I think it’s the best drumming he’s ever done. It’s snappy!,” Rancourt cackles. Two guitars—Fleming and the always in motion Gary Lucas (Captain Beefheart, Jeff Buckley, Gods and Monsters) laying a carpet of flowers and fugg over everything they touch. It’s glorious. “It was so much fun to see Don doing the Ron Asheton thing and Gary Lucas putting flamenco flourishes on top of the cake,” he says.

plum plum is an album that loosely references New York then and now. There’s a song about no wave icon Pat Place, and “She Got Hit” is a side-door tribute to Lou Reed—it’s “Sister Ray” for the era of the Second Avenue Subway. “Leave Your Light On” was written, Rancourt says, for Dolly Parton to sing, and she should, too, preferably greeting a boat of new immigrants at the Statue of Liberty. Kim says “Arkansas is Burning” is his favorite song, a pink pussy hat of a protest against political stupidity. Some protest songs don’t get dated.

He was born and bred in Royal Oak, Michigan, and baptized in Soupy Sales, Rita Bell, Johnny Ginger and Swingin’ Time With Robin Seymour. He was raised in the shadow of Father Coughlin’s Shrine of the Little Flower and graduated from a high school named after a senator who thought artists were Communists. There was a lot to rebel against. And from an early age, Rancourt has usually been about the biggest fan in the room. He says “I have always been a fanatic, ever since my father brought home for me the 45 of ‘The Flying Purple People Eater.’” A few years later, he was sitting on the front porch with some buddies while the Beatles landed at Laguardia. There was a live feed broadcasting the arrival on Detroit radio. “The panic, all the girls screaming—boom, that changed me. It was, Off to the record store.”

He saw the Motown Review perform at the Michigan State Fair, and caught Glen Frey’s band The Mushrooms at Helen Keller Junior High. Wait, what? He heard numerous shows at the Royal Oak Farmer’s Market, and he once stole a red dog collar from local Kroger’s so he could be dressed right for the Brownsville Station/Stooges show. In college he directed the only authorized stage production ever of a Firesign Theater album. A theme emerges: loud and cracked saves lives.

He had a vision at the Detroit Institute of Arts, staring at James McNeil Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket until the missiles hit the mist. It blew his mind the way Mitch Ryder had, and launched an obsession with Whistler that led him to enter the Whistlers Study Program at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. In recent years he has been working on a musical of the life of Whistler.

In 1974 he made it to New York; dishwashing and amazing encounters with idols ensued. Slowly, a band came together. When People Were Shorter and Lived Near the Water, the first group he led (with Joe DeFillips), debuted on the boardwalk at Coney Island. They were funny and hostile and conceptual—Rancourt jamming a Joe Besser hoot and a joe mama howl while covering Abraham Lincoln, Bobby Goldsboro, Gershwin and a few other nice things. Karen Schoemer, The New York Times: “this group’s love of bad taste seemed honest and heartfelt.” In a few years his soul migrated to The Shapir‑O’Rama, a crashing, unraveling guitar band that put out three fine albums (two with Jad Fair also on mic). It was the sound of bad old ideas being torn down and children playing in their rubble. Robert Christgau, The Village Voice: “Rancourt sings several of the best soliloquies here all by himself.”

Today Rancourt can do midtown, he’ll show you the Village, but truly his specialty is Coney Island. His lovely wife Rona took him there on an early date and “I just fell in love with it,” he explains. “It was seedy and dangerous like Times Square was,” and there was an incredible little community of sideshow performers that were like nobody else in New York City. “It’s a never-ending history lesson and I’m learning something all the time whether it’s from an old timer or Woody Allen filming his new movie, ‘Wonder Wheel’ there.” An end and a beginning.

And on Sundays, he’ll be down there on the beach smoking a cigar, with an eye out for whatever’s washed up today. “Walking the Trashline” is the first song on plum plum, and it’s one of the best. He’s walking and talking, same as ever, sounding thrilled to be alive, thrilled to be surrounded by all this human-made stuff that he sees potential in. Total tiny.

R J Smith 2017